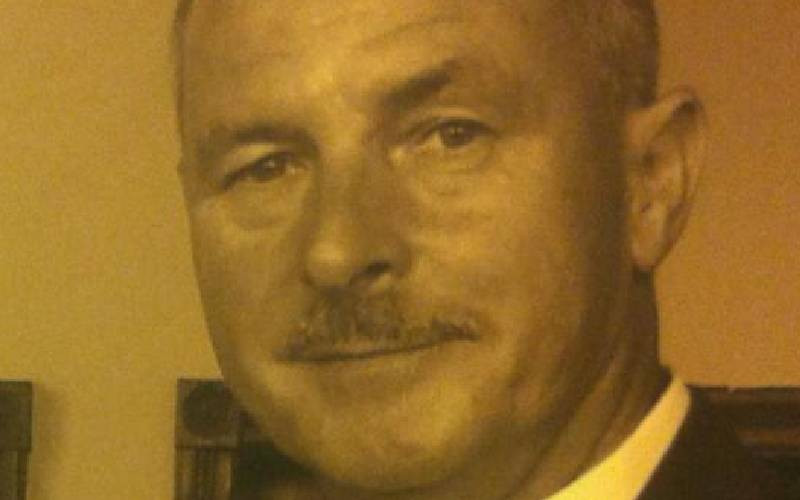

The Mombasa Law Courts last week declined to decide the final resting place for UK tycoon Roy Veevers whose kin is fighting to have him buried in the UK or Mombasa.

Roy did not leave behind a will dictating his final resting place.

The situation mirrors cases of many families that have been caught standoff when their loved ones die and the kin fight over the right to bury them.

Roy’s sons Richard Veevers and Philip Veevers from his first marriage want their father buried in the UK while his daughters Hellen Veevers and Alexandra Veevers from the second marriage want him buried in Mombasa, Kenya.

Roy’ body has remained in the morgue for 11 years following an inquest into his death, with the sons accusing their mother-in-law and their sisters of allegedly poisoning their father.

In his ruling, dated August 13 2025, Senior Resident Magistrate David Odhiambo said that deciding the final resting place for Roy is nerve-wracking but has to be done anyway.

"Oh Roy, son of Ruth Veevers, you left us confused, but we won't disappoint you; just wait!" said Justice Odhiambo

He said that Roy did not subscribe to any customs in Kenya, where he had settled with his second wife, Azrah Din Parveen, and his two daughters, Hellen Veevers and Alexandra Veevers.

Odhiambo said that Roy did not leave a will to show how he wished to exit the world, nor was there evidence adduced to remove any of his family members by the dint of proximity.

The magistrate also said that there was no evidence to show that he had a sour relationship with any of his close family that would exclude them from claiming the body.

“It is for this reason that deciding the final resting place for Harry Roy Veevers is quite nerve-wracking. It is a tough decision that someone has to make anyway,” said Odhiambo.

“It is tough because Roy Veevers was a mzungu who did not subscribe or bind himself to any custom; no evidence was adduced to remove any close family member from his legal proximity; no evidence was adduced in the form of a will to show that he wished to exit the world in a certain way or show that he had a sour relationship with any of his close family members so as to exclude anyone from claiming the body,” he added.

Similarly, in June 25 2025, Senior Principal Magistrate Peter Ndege ordered the release of a man's body to his widow in a disputed Kisii burial rite with the late deceased's brothers.

Jeniffer Kemuma had applied for orders to bury her late husband, Benson Momanyo, at their matrimonial home in Nakuru.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

However, his brothers wanted Momanyi to be buried at his ancestral land in Kisii according to Kisii custom.

The magistrate determined that Kemuma, reserved the right to bury the husband.

Momanyi's brothers Lukas Makori, Kennedy Makori, David Makori, Josphat Makori and Jared Makori argued that their late brother wanted to be buried in Kisii, where his two children were buried.

In 2010 former Chief Justice David Maraga ruled that a widow or widower accrues rightful ownership to bury his or her deceased spouse.

Justice Maraga said the wishes of a deceased as to where to be buried and other circumstances override the wife or husband' right to bury their spouse in their matrimonial home.

While analysing burial disputes, Odhiambo noted that Kenya has no comprehensive legal provision in Kenya on the procedure for handling, disposing of or settling of disputes relating to the dead or burial of persons.

Odhiambo said that only Section 137 of the Penal Code, which makes it an offence to hinder the burial of the dead, provides that whoever unlawfully hinders the burial of the dead body of any person without lawful authority is guilty of a misdemeanour.

He submitted that most people make provision in their wills on how they wish their bodies to be disposed of upon demise, but the executor of the wills is not bound if the wishes are unworkable or in conflict with the personal laws of the deceased.

“There is no ownership or property in a dead body that can be transferred to another through a will. The expressions in the will therefore just remain that, expressions,” said Odhiambo.

He noted that due to conflicting wishes of the dead and the living, disputes often arise, leading to court cases that drag for months or even years, causing financial and emotional burdens to be placed on the families involved.

Odhiambo said that in determining burial disputes between families, the court is usually guided by the religion of the deceased.

However, he argued that Kenya presently does not have legislation guiding burial disputes in Kenya.

The magistrate observed that the Kenya Law Reforms Commission has proposed enactment of legislation that should revolve around the disputes.

He said that Kenyan courts have focused on common law principles like judicial precedence while attempting to interpret customary law in resolving burial disputes.

“In sudden violent deaths, English courts have occasionally favoured the person who wants the deceased laid to rest away from the scene of the tragedy,” said Odhiambo.

He observed that in the Luo community, an adult man will be buried depending on the clan from which he hails. Even if the man may have in his life expressed a wish for his place of burial, the wish will be subject to the customs and traditions of his clan.

“The clan sages are not necessarily bound to comply with those wishes if they do not conform to the customs and traditions of the clan. The court therefore set precedent by giving the body to the clan for burial at his ancestral home in Western Kenya,” said Odhiambo.

Odhiambo found that precedence continued to impact burial disputes in Kenya for a long time, including the burial of the Tugen clan based on customary law.

In Tugen customary law, a man must be buried by his father and family members at his ancestral home. Odhiambo also pointed out the courts consider the proximity of the deceased to the disputed parties.

He said that generally the marital union will be found to be the focus of the closest chain of relationships touching the deceased.

“Accordingly, the right to bury a dead body can only be conferred to the person who is able to demonstrate the closest proximity to the deceased,” said Odhiambo.

He said the courts can also focus on the wishes of the deceased person.

Odhiambo cited a case where the High Court allowed the deceased to be buried in a Muslim cemetery based on his will and rejected his mother’s attempt to bury him in his Kisii ancestral home subject to Kisii customs.

The fourth option involves the court considering the relationship between the deceased and the litigants in the burial dispute.

He argued that in the fourth option, a person with whom the deceased has a sour relationship cannot be allowed to bury him/her.

“It means that the mistreatment of the deceased while alive by a litigant negates his/her customary right to bury her/him,” said Odhiambo.